Run Time Data Structures¶

Introduction¶

This document explains how the compiler allocates memory for variables in a program. First it is necessary to understand the requirements and the underlying theoretical concepts in some detail.

The storage allocation Problem¶

A program contains global variables as well as variables that are local to functions, both requiring memory space. Of these, global variables are the simplest to handle because during the analysis phase we know how many global variables are there in the program (all global variables are declared) and how much space needs to be allocated for each of them (why?). Thus, the storage requirements for global variables are completely determined at compile time and they can be assigned memory addresses during the analysis phase itself. Such allocation is called static allocation. The binding field of the global symbol table entry for a variable is set to the memory address allocated to the variable. This symbol table information will be used during the code generation phase to find out the address of the variable in memory.

During the analysis phase the compiler will not decide on the addresses in the code area of memory where a function's code is loaded. Hence, the compiler cannot fix the address to which function must be attached. To handle this issue, the compiler will assign a pseudo address to each function, which will be stored in the binding field of the function's global symbol table entry. All calls to the function will be translated to an assembly level call to this pseudo address. The correct addresses will be assigned later during label translation.

Variables which are local to functions demand more complicated allocation. This is because a function may be invoked several times and for each invocation, separate storage needs to be allocated for variables defined within the scope of the function (i.e., local variables and arguments). [Why?] Moreover, we do not know during the analysis phase how many times a function will be invoked during the execution. Why?

To understand this, consider the factorial program below.

decl

int result,factorial(int n);

enddecl

int factorial(int n){

decl

int f;

enddecl

begin

if( n==1 || n==0 ) then

f = 1;

else

f = n * factorial(n-1);

endif;

return f;

end

}

int main(){

decl

int a;

enddecl

begin

read(a);

result = factorial(a);

write(result);

return 1;

end

}

The function factorial contains an argument 'n'. Suppose the initial value of 'n' input by the user at run time was 5, then factorial(n) with n=5 is invoked from the main. This function invokes factorial(n) with n=4. However, we need to retain the old value of n since the orginal factorial function must resume execution after the completion of factorial(4). Thus, we cannot statically assign a fixed memory address to the variable n. Instead, for each invocation of the function, we need to create a different memory space for storing the value of n. Moreover, the initial value of n given by the user is not known at compile time. Hence, we cannot determine at compile time the exact storage requirements. The compiler should generate code in such a way that necessary memory space is allocated at run time as required.

In addition to allocating storage for local variables and arguments, additional storage needs to be allocated at run time for each invocation of a function to store the return values of the call and control information like a pointer to the next instruction in the calling function (return address).

The classical solution to handle the above problem is to maintain a run time stack. Whenever a function is invoked during execution, an activation record is created in the run time stack with sufficient space for storing local variables, arguments, return values and return address, and the stack grows. Upon return from the function, the activation record is popped out of the stack and the stack shrinks, leaving the activation record of the calling program at the top of the stack. Thus, at each point during execution, the activation record of the currently executing function will be on the top of the stack. Such storage allocation is called stack based run time allocation.

[Note: The semantics of ExpL makes stack based allocation possible. Primarily, this is possible because data stored in an activation record can be forgotten once the execution of the call is finished. There are languages like LISP which permit higher order functions where a stack based run time allocation is not possible. Languages which permit stack based run time allocation for function invocations are said to follow stack discipline.]

Observe that for each function defined in an ExpL program, the amount of storage needed in its activation record is known during the analysis phase. [Why?] What is not known is how many activation records will have to be created in the stack as this is known only during execution time.

In addition to allocating storage for global variables and variables local to functions, ExpL supports dynamic memory allocation through the alloc() function. The alloc() function allows a program to request for memory space at run time. Since the amount of memory requested is not known during the analysis phase (why?), static allocation is not possible in this case. Stack allocation also is ruled out because memory allocated by alloc() inside a function is not de-allocated when the function returns. Hence, a mechanism to dynamically allocate memory on demand at run time is required.

The classical solution to this problem is to maintain a contiguous area of memory called the heap memory from which memory is allocated by alloc() on demand. Heap management algorithms like the fixed size allocator algorithm and the buddy system algorithm are explained in detail later in this documentation.

Finally, intermediate values generated during program execution needs temporary storage. For example, while evaluating an expression (a+b)*(c+d), the values of the sub-expressions (a+b) and (c+d) might need temporary storage. The machine registers are used for temporary storage. When a function invokes another function, the registers in current use will be pushed to the stack (activation record of the caller) so that the called function (callee) has the full set of registers free for its use. Upon return from the callee, the values pushed into the stack are restored to the registers before the caller resumes its execution.

To summarize, we have four kinds of memory allocation – static, stack, heap and register (temporary). The implemention of each of these are discussed below.

The memory model¶

The compiler assumes an address space model for the target program, determined by the target machine architecture as well as the target operating system.

The memory model provided for application programs running on the Experimental Operating System(eXpOS) for the XSM machine architecture is explained below. For further details, see the Application Binary Interface(ABI) Specification documentation.

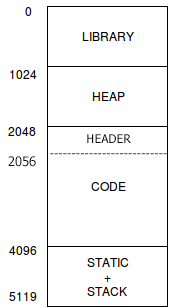

The figure shows that the target code generated by the compiler will be loaded to memory addresses 2048 to 4095 (total 2048 memory words). Since each XSM instruction occupies two memory words, the target program can have at most 1024 machine instructions.

Since the XEXE executable format stipulated in the eXpOS ABI does not provide separate memory areas for static and run time data, the compiler must allocate both static variables and run time stack between memory addresses 4096 and 5119. The recommended convention is to allocate global variables in the initial portion of this memory and then the run time stack may be initialized to the top of this data so that it can grow upward during run time. Note that the target program must contain instructions to initialize the run time stack. This is because eXpOS does not initialize the stack pointer when the program is loaded for execution. The OS instead expects the loaded executable to contain instructions to set up the stack.

When an XEXE executable file is loaded by the OS into the memory, the OS loader will link a collection of pre-loaded routines in memory (called the library to the address space of the newly loaded program. These routines include the dynamic memory routines - alloc(), free(), Initialize() and input-output routines read() and write(). This makes compiler design easy because the compiler just has to translate any high level invocation of the above functions to low level calls to the corresponding library routines. The details of how to generate code to invoke library routines is specified in the library interface. [Note 1: You can design and implement the library routines yourself in ExpL and install your library routines into the OS so that OS uses your routines as its library.] [Note 2: The first eight words of an XEXE executable contains a header. One of the fields in the header is a library flag. While preparing the executable file, the compiler must set this flag bit to tell the OS loader that the library must be linked to the address space at the time of loading the program] The library routines for alloc(), free() and initialize() as implemented in eXpOS library uses the heap region in the address space for managing dynamic memory. Hence, the compiler must not allocate its own variables in this space. The static and runtime memory allocation by the compiler can instead use the stack region, as described previously.

Finally, the XSM machine provides 20 registers R0-R19 for storing temporary values. The machine requires operands to be loaded to registers before doing arithmetic/logical operations.

In the following, we describe how activation records are allocated in the stack, how the library routines for Alloc() and Free() must manage heap memory and how the compiler may allocate registers for temporary storage.

Temporary Allocation¶

Register allocation is performed through two simple functions. int get_register()...

Static Allocation¶

Global variables are allocated statically. In our interpreter, the initial portion of the stack will be used for ....

Run time Stack Allocation¶

During run-time, when an ExpL function is invoked, space has to be allocated for storing the arguments of a function, return value...

Heap Allocation¶

ExpL specification stipulates that variables of user defined types are allocated dynamically using the alloc() function. The alloc() function has the following syntax: .... Read more